ch11: Client Identification and Cookies

1. The Personal Touch

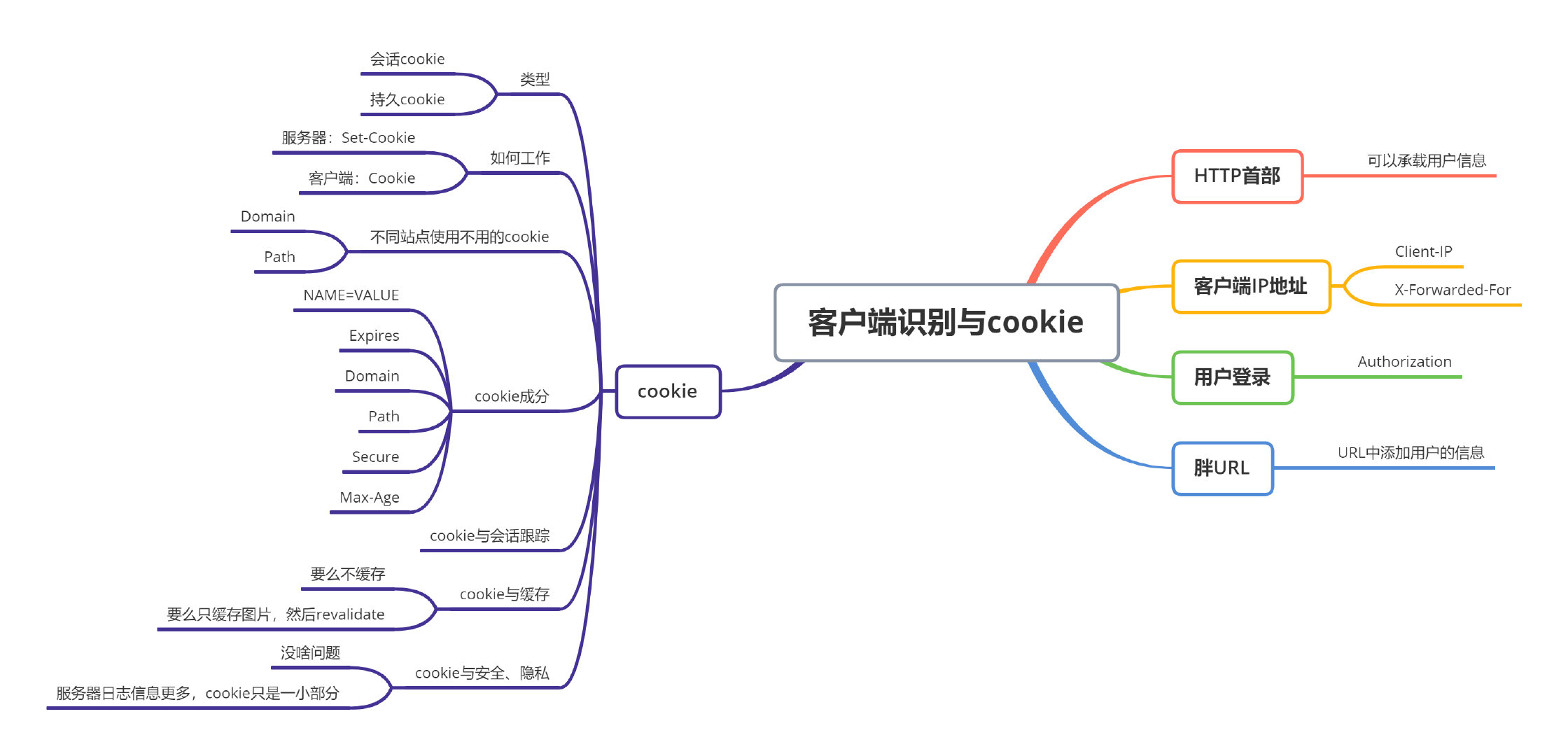

Mechanisms to identify users:

HTTP headers that carry information about user identity

Client IP address tracking, to identify users by their IP address

User login, using authentication to identify users

Fat URLs, a technique for embedding identify in URLs

Cookies, a powerful but efficient technique for maintaining persistent identity

2. HTTP Headers

HTTP headers carry clues about users:

Header name

Header type

Description

From

Request

User's email address

User-Agent

Request

User's browser software

Referer

Request

Page user came from by following link

Authorization

Request

Username and password

Client-ip

Extension(Request)

Client's IP address

X-Forwarded-For

Extension(Request)

Client's IP address

Cookie

Extension(Request)

Server-generated ID label

3. Client IP Address

Limits:

Client IP addresses describe only the computer being used, not the user.

Many Internet service providers dynamically assign IP addresses to users when they log in.

The Network Address Translation (NAT) devices obscure the IP addresses of the real clients behind the firewall.

HTTP proxies and gateways typically open new TCP connections to the origin server.

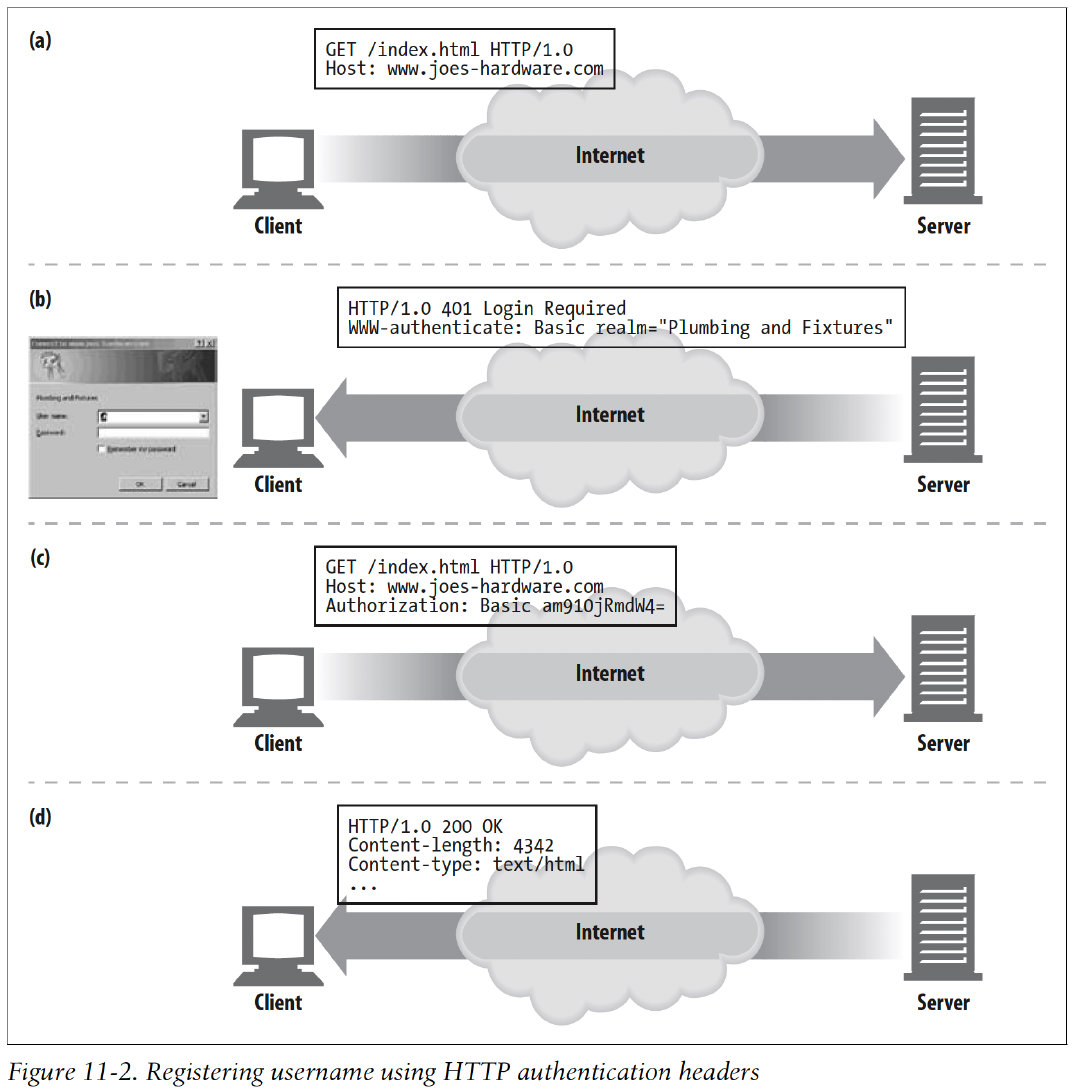

4. User Login

Flow:

5. Fat URLs

Some web sites keep track of user identity by generating special versions of each URL for each user.

URLs modified to include user state information are called fat URLs.

Problems:

Ugly URLs: the fat URLs displayed in the browser are confusing for new users.

Can't share URLs: the fat URLs contain state information about a particular user and session.

Breaks caching: Generating user-specific versions of each URL means that there are no longer commonly accessed URLs to cache.

Extra server load: the server needs to rewrite HTML pages to fatten the URLs.

Not persistent across sessions: All information is lost when the user logs out, unless he bookmarks the particular fat URL.

6. Cookies

Cookies are the best current way to identify users and allow persistent sessions.

6.1 Types of Cookies

session cookies

persistent cookies

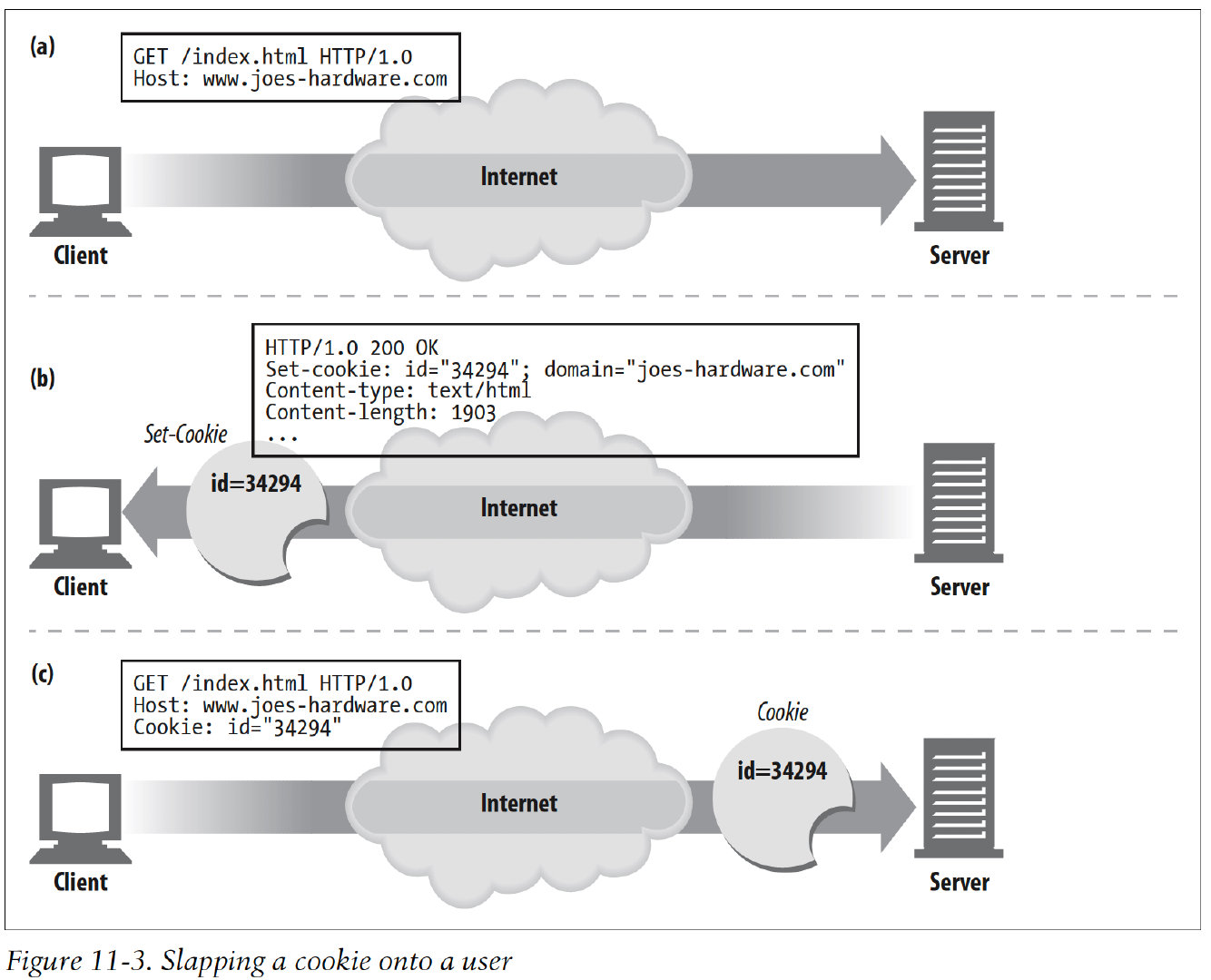

6.2 How Cookies Work

6.3 Cookie Jar: Client-Side State

The basic idea of cookies is to let the browser accumulate a set of server-specific information, and provid this information back to the server each time you visit.

The browser is responsible for storing the cookie information, this system is called client-side state.

6.4 Different Cookies for Different Sites

A browser typically sends only two or three cookies to each site.

In general, a browser sends to a server only those cookies that the server generated.

6.4.1 Cookie Domain attribute

A server generating a cookie can control which sites get to see that cookie by adding a Domain attribute to the Set-Cookie response header:

If the user visits www.airtravelbargins.com, the following Cookie header will be issued:

6.4.2 Cookie Path attribute

A special auto-rental cookie might be generated like this:

If the user goes to http://www.airtravelbargains.com/specials.html, she will get only this cookie:

But if she goes to http://www.airtravelbargains.com/autos/cheapo/index.html , she will get both of these cookies:

6.5 Cookie Ingredients

There are two different versions of cookie specifications in use.

6.5.1 Version 0 (Netscape) Cookies

Format:

Attributes:

Set-Cookie attribute

Examples

NAME=VALUE

Set-Cookie: customer=Mary

Expires

Set-Cookie: foo=bar; expires=Wednesday, 09-Nov-99 23:12:40 GMT

Domain

Set-Cookie: SHIPPING=FEDEX; domain="joes-hardware.com"

Path

Set-Cookie: lastorder=00183; path=/orders

Secure

Set-Cookie: private_id=519; secure

Secure: if this attribute is included, a cookie will be sent only if HTTP is using an SSL secure connection.

6.5.2 Version 1 (RFC 2965) Cookies

The RFC 2965 cookie standard is a bit more complicatead than the original Netscape standard and is not yet completely supported.

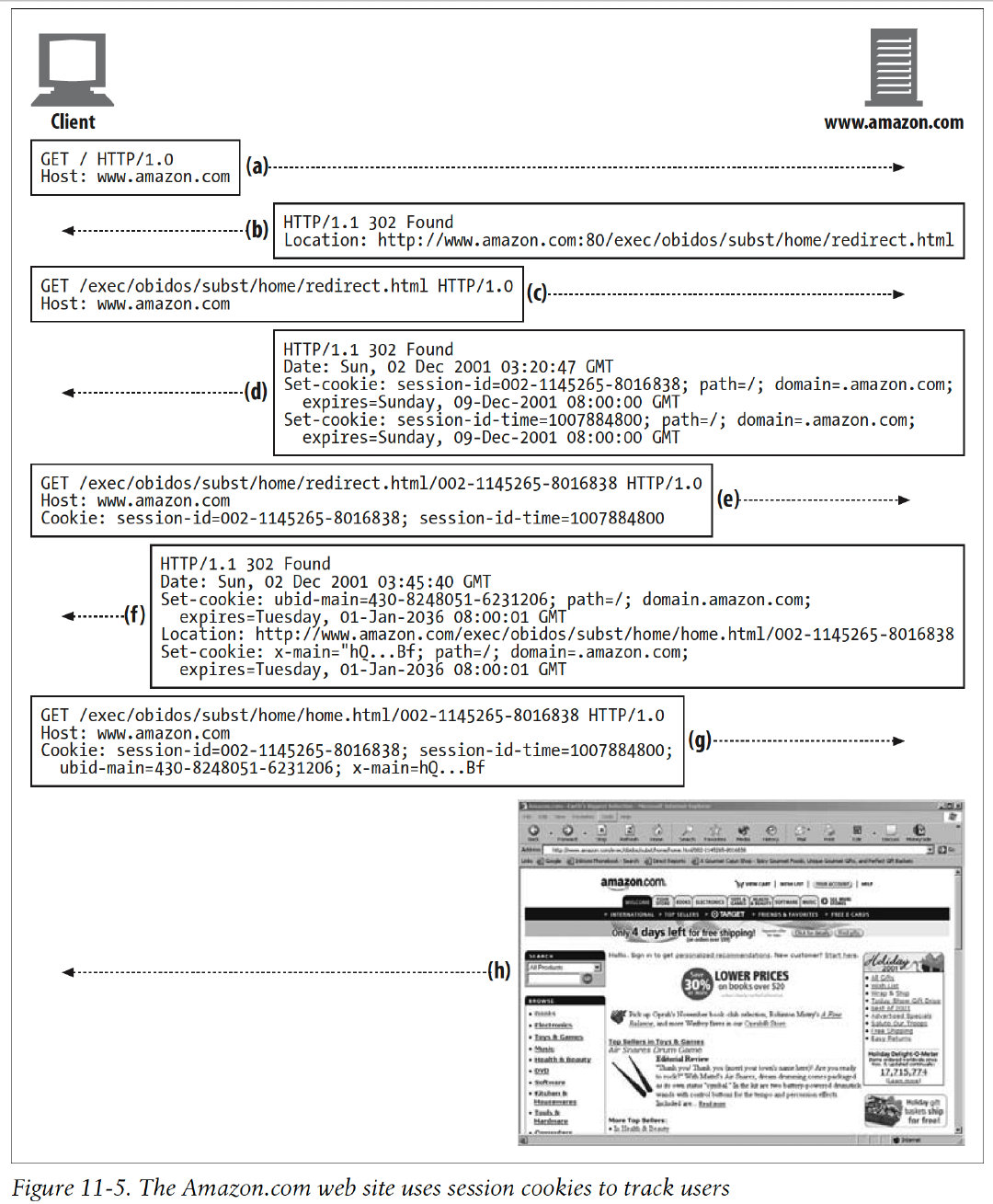

6.6 Cookies and Session Tracking

6.7 Cookies and Caching

You have to be careful when caching documents that are involved with cookie transactions.

Here are some guiding principles for dealing with caches:

Mark documents uncacheable if they are: Cache-Control: no-cache="Set-Cookie", Cache-Control: public

Be cautious about caching Set-Cookie headers:

6.8 Cookies, Security, and Privacy

Cookies themselves are not believed to be a tremendous security risk, because they can be disabled and because much of the tracking can be done through log analysis or other means.

Last updated